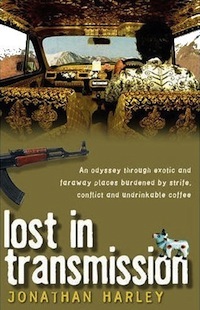

Lost in Transmission

Gritty adventures and near misses in India on a shoestring budget. India is a poor man's America.

With the September 20, 2008, news that a hotel in Islamabad, Pakistan had been bombed, I knew exactly which one they meant—the Marriott. I had just finished reading Jonathan Harley’s Lost in Transmission. Harley’s book is a memoir of his time in New Delhi, India as South Asia Bureau Chief for Australian Broadcasting Company (ABC).. During his three year tour of duty, he frequently passed through Islamabad and would meet fellow journalists at the Marriott.

With the September 20, 2008, news that a hotel in Islamabad, Pakistan had been bombed, I knew exactly which one they meant—the Marriott. I had just finished reading Jonathan Harley’s Lost in Transmission. Harley’s book is a memoir of his time in New Delhi, India as South Asia Bureau Chief for Australian Broadcasting Company (ABC).. During his three year tour of duty, he frequently passed through Islamabad and would meet fellow journalists at the Marriott.

A bastion of brass and marble, “Islamabad’s Marriott Hotel foyer zips with the ditzy rings of mobile phones as beautiful young women in elegant salwar kameez sip tea in the cafe. This is the place to be in Islamabad. Actually it is the only place in Islamabad—another five-star hotel is slowly on the way, but for decades the Marriott has held tight its monopoly over foreign visitors and Islamabad’s wealthy.”

Lost in Transmission is the telling of a journalist’s gritty adventures and near misses during a very difficult time in history. ABC apparently sets Harley loose to cover all of south Asia on a shoestring budget, so his story is all the better for his inventiveness and creativity on getting to the story with little financial or technical support from the network (unlike the major international network reporters who travel in style with a cadre of technicians.) Undeterred, Harley gets the story filed one way or another.

His narrative covers 1998-2002, a period of great upheaval in that part of the world. Harley has the challenging and fascinating task of bringing the news to the Aussies back home.

Harley is close by when Australian missionary Graham Staines and his two sons are murdered in the state of Orissa. He makes his way via taxi to the backwater village of Baripada, a ten hour ride from Calcutta. “Beyond huddles of people weeping and praying, an arc of camera lights glare on Gladys Staines. The most recent widow in India sits calmly, almost serenely, patiently fielding reporters’ questions. Perhaps she has not had time to cry or she is waiting for some privacy. She’ll wait forever. Like most things in India grieving is a public event.”

When cricket legend Don Bradman dies, Harley is on the spot in a cricket crazed country to get local fans’ reactions as well as that of the Australian cricket team coincidentally on tour in India.

Harley sprints to Kathmandu, Nepal, when the king is murdered. He sneaks into the Jalozai, Pakistan, refugee camp for Afghans to get a story on the conditions there. He secretly and illegally shoots video in Kabul at a soccer game and attends a teetotaling, underground Kabul club where the men watch movies and listen to music despite the Taliban’s prohibition of such activities. Constantly traveling, Harley follows one breaking story to next.

Some of Harley’s conclusions are astute, others endearing.

Referring to the technical challenges he faces, such as having no camera crew or the unreliable flow of electricity, he writes, “In India no one can hear you scream.” So he concludes he will just have to figure it out himself, something new to this, then, 28 year old reporter.

In Kashmir, he travels to the front lines of the on-again-off-again border conflict over boundaries and is faced with firsthand war and weaponry for the first time: “A doctor friend once told me that medicine makes him feel stupid because there is so much to learn. That’s how I feel now. I know nothing about the deafening hardware in front of me. I want to call everything that is loud and terrifying ‘bombing’. I can see that the big bullets go in the big guns and make a big bang and presumably kill big groups of people. But that won’t give my reports any authority.”

Of India’s stereotypes and cliches, Harley writes: “…India stares down its cliches, sticks out its tongue… to the stereotypes. It is the richest, poorest, most charming, infuriating, beautiful and hideous land in the history of time. And it can be as efficient as it can be chaotic. I am learning a universal and merciful law of the land: everything you say about India is right and so is its opposite.”

Harley calls India a poor man’s America. “…the more I see India, the more I see the United States. Both great nations share an unshakable sense of historical destiny; they each take immense pride in their democracy, social diversity and incredible cultural creativity. Their nation’s imaginations are captivated by their prolific and usually trashy film industries. Both peoples take themselves far too seriously and take refuge in jingoism…They each boast massive armies and nuclear arms. And in both societies, those with power and money are respected and fawned upon in a way that rubs against Australian anti-authoritarianism. In short, both countries believe they’re the center of the universe.”

One of the reasons this book particularly appeals to me is the distinctly non-North American viewpoint. Harley openly airs his take on all things American including journalists, politics, and culture. It is refreshing to hear from someone other than one of ‘us’.

Harley is one of the few foreigners in Kabul on September 11, 2001. He is covering the trial of detained American aid workers when the scene suddenly shifts to the Twin Towers in New York City. In a media starved city, Harley and the other correspondents scramble to piece together the story of what is happening in the United States. He ends up at the United Nations house, the only place in town permitted a television. Shocked into silence and disbelief, the room fills with those seeking television coverage. The next day the UN is evacuating all nonessential staff and offers leftover seats to journalists wanting to leave Afghanistan. Harley vacillates between staying which is his preference and leaving which everyone else wants him to do including his wife and his ABC boss. He leaves Kabul and winds up at the Marriott Hotel in Islamabad.

At an anti-American rally the next day, he is confronted by a protestor, “...a young beard runs up and screams straight in my face. ‘You American dogs tell your President: attack Afghanistan and he will die!!’ He is so in my face I can feel his hot breath in my nostrils.”

“I’m not American!” I scream back. “I’m Australian!”

“‘Australia?!?’ His anger shifts to surprise, then delight, ‘Oh!! Steve Waugh first-class captain! Very good! welcome to Pakistan!” He turns and dissolves into the crowd.”

This is just one of many examples of the preposterous circumstances Harley faces during his tenure as South East Asia bureau chief for ABC. Lost in Transmission is brimming with them. It is a great read providing background to what is going on in the middle east now, but as mentioned before, it is from a non-U.S. perspective. Harley has an easy to read writing style making this an intelligible book while covering difficult subject matter.

J.S. Maverick

Get "Lost in Transmission" from Amazon.com

See also my review of Holy Cow: An Indian Adventure by Sarah MacDonald, Jonathan Harley’s wife. She gives a completely different view of the same time that she and Jonathan lived in Delhi.)