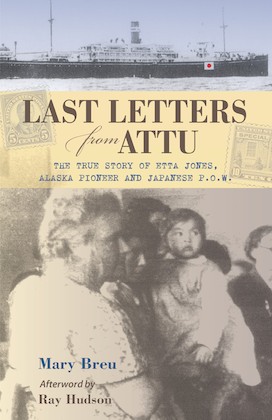

Last Letters from Attu: The True Story of Etta Jones, Alaska Pioneer and Japanese POW

Etta Schureman migrated to Attu Island in the Aleutians, taught school, married Foster Jones and went to Japan as a POW in 1942 after the Attu invasion.

by Nancy Kerstetter

Etta Schureman arrived in frontier Juneau, Alaska, in 1922. A scrappy, independent single woman, the 43-year-old accompanied her school teacher sister Marie to a new teaching position. Etta stayed on for 20 years. Overwhelmed by the isolation, Marie returned to the East Coast when her contract expired one year later. By that time, Etta had met and married the love of her life—Charles Foster Jones.

Grandniece Mary Breu reconstructs Etta’s life story in Last Letters from Attu: The True Story of Etta Jones, Alaska Pioneer and Japanese P.O.W. Author Breu based the story on a manuscript Etta wrote about her life in Alaska plus her personal letters. Breu also interviewed and corresponded with Etta’s fellow POWs. Unfortunately, the book was written long after Etta’s death so she could not be consulted regarding details. Possible knowledgeable contacts or witnesses had difficulty reconstructing the details since so much time had passed. The lack of detailed resource materials shows in some of the writing.

Grandniece Mary Breu reconstructs Etta’s life story in Last Letters from Attu: The True Story of Etta Jones, Alaska Pioneer and Japanese P.O.W. Author Breu based the story on a manuscript Etta wrote about her life in Alaska plus her personal letters. Breu also interviewed and corresponded with Etta’s fellow POWs. Unfortunately, the book was written long after Etta’s death so she could not be consulted regarding details. Possible knowledgeable contacts or witnesses had difficulty reconstructing the details since so much time had passed. The lack of detailed resource materials shows in some of the writing.

The book has two definitive parts. Part one narrates Etta’s early years, education and family life before Alaska. It also includes absorbing details about the 20 years Etta and Foster taught and worked together in the frontier territory. Although mail delivery was erratic and spaced out—sometimes they received mail delivery only every three months—Etta was an ardent letter writer. Living in rustic surroundings, often without electricity or telephone, Etta connected to the outside world through correspondence. Her family must have treasured her letters because they survived over 60 years to help Breu write Etta’s story.

One interested incident involves the dog teams and sleds owned by the Etta and her husband. At one time, both Foster and Etta had their own dog sled teams. Many women had their own teams. Foster thought her dogs were too small, but she loved them and they worked well for her. She recalls the time she accompanied Foster and a prospecting partner on the first few miles of a trip. The dogs were rambunctious and she worried whether any of the eggs she was carrying for the men were still intact. They laughed it off reminding her about the difficult in breaking frozen eggs.

The books becomes vague and fuzzy in part two as many details have been lost over time. In June 1942 the Japanese arrive at Attu, the most westward island of the Aleutians. The Jones had been at Attu for less than a year working with a small band of Aleuts whom Etta describes as quiet, dignified and rugged. She served as a school teacher and Foster relayed regular weather reports to the U. S. government. The tranquility of the hard-working community shattered on Sunday morning, June 7. “As they (the villagers) looked at the mountains that normally sheltered their homes, they were horrified to see armed men in unfamiliar uniforms, slipping, sliding, and running down the snow-covered side of the mountain, all the while shrieking and shooting their guns,” writes Breu.

Foster was finishing the morning weather report via radio as bullets began raining on the Jones’ home. He added four words: “The Japs are here!” That was the last the outside world heard from Attu for quite some time. No one knew what transpired on Attu until after the war ended and Etta was repatriated.

She was separated from Foster from that day on, she said her faith in God sustained her through what became years of hardship and neglect.

With one hour’s notice, she gathered some belongings before departing for Japan by ship. She joined Australian nurses captured at Rabaul. The 19 of them became a close knit community of Allied women prisoners held together for over three years. First they were held in Yokohama and later in a small compound at rural Totsuka, outside Yokohama.

Etta was 63 years old when taken prisoner. The nurses were much younger and looked to her for courage and guidance. She was able to supply this from her pioneer experiences of roughing it in Alaska. Once the Japanese were dispensing sanitary napkins to the internees. They did not give Etta any presumably due to her age. She insisted she get some as well indicating it was only fair, but she was really getting them so she could share with the gals.

Later on, the sanitary napkins were valued for a secondary use. One of the captive nurses was very weak and suffering from exposure to the cold–the Japanese did not provide warm clothing to the prisoners–so the women knitted a sweater for her from the napkin fibers. The resourceful inmates pulled cotton strands from the sanitary napkins, then rolled them with silk threads leftover from a work project to make ‘yarn.’ They rubbed the two strands together using the palms of their hands to create a special fiber. The nurses had watched South Pacific natives roll fibers to make thread and they successfully mimicked the process.

In July1945 the Red Cross learned of about the female prisoners and visited them. Before then, they had received no letters, no supplies, nothing to help them survive the ordeal of a primitive Japanese POW camp. No one in the world knew what had become of them or where they were held, except their Japanese captors.

When U.S. General Douglas MacArthur’s motor convoy roared through Totsuka en route to Tokyo from nearby Atsugi Airfield, the women knew for certain that the war was over. They were rescued that same day by one of MacArthur’s officers, Major William Meanley, who saw them standing roadside.

The remainder of the book rambles briefly about Etta’s return to the U.S. and reunion with her family. She steadfastly refused interviews about her internment, preferring to focus on her pioneer life in Alaska. Her POW years were too painful to think or talk about, so she did not.

This book would make a happy companion for travelers to Alaska, a popular destination for vacationers. Pair it with a book of Robert Service poetry for a total Alaskan experience. Etta loved the stark beauty of the landscape. Read her story and imagine how it was in the good ol’ days, or wonder about the POW’s extravagant relief and astonishment as they witnessed the motorcade of U.S. soldiers passing through their dreary village. Pair this book with viewing the current release of “Emperor” at the theater for a World War II tie-in.

You can obtain this book from your local library, inter-library loan or Amazon as a paperback or Kindle book.