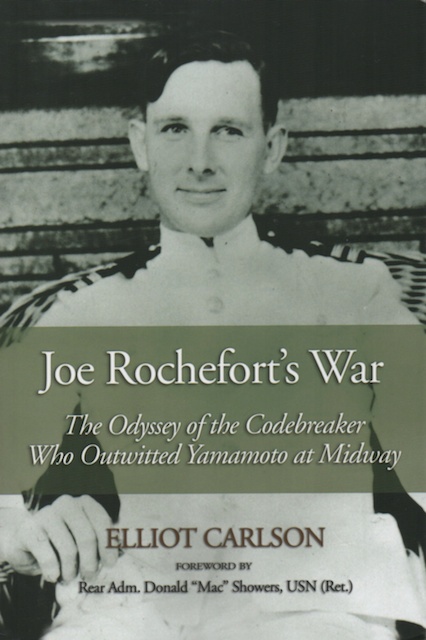

Joe Rochefort's War

A maverick codebreaker, Rochefort motivates his team to relentless pursuit of interpreting the coded messages of the Imperial Navy.

by Nancy Kerstetter

Naval authorities pass over Joe Rochefort’s nomination for a Distinguished Service Medal in 1942. The idea that his recognition is sabotaged by spiteful Navy personnel in Washington DC lurks in the background. Finally in 1986, President Ronald Reagan awards it to him posthumously. What he should collect 44 years earlier, his son and daughter receive on his behalf. You may wonder how this happen, especially since Admiral Chester W. Nimitz mades the original recommendation. The busyness of the war in the Pacific and the modest attitude of Rochefort himself are two substantial reasons why it is pursued at the time.

Elliot Carlson, author of Joe Rochefort’s War: The Odyssey of the Codebreaker Who Outwitted Yamamoto at Midway, details the Naval career of Rochefort, a maverick codebreaker who motivates his team of experts to relentless pursuit of interpreting the coded messages of the Imperial Navy. Based at Pearl Harbor, Rochefort and Station Hypo—Rochefort’s team of intelligence specialists—are one of three units receiving and attempting decryption of the numerous communications sent to and from Japanese naval command.

Elliot Carlson, author of Joe Rochefort’s War: The Odyssey of the Codebreaker Who Outwitted Yamamoto at Midway, details the Naval career of Rochefort, a maverick codebreaker who motivates his team of experts to relentless pursuit of interpreting the coded messages of the Imperial Navy. Based at Pearl Harbor, Rochefort and Station Hypo—Rochefort’s team of intelligence specialists—are one of three units receiving and attempting decryption of the numerous communications sent to and from Japanese naval command.

His role in alerting the Navy command of the impending raid at Midway is the impetus for his nomination for the Distinguished Service Medal. He and his crew unravel enough of the intercepted communications to figure the time, objective and attack force heading to Midway. At the same time other branches of the broader naval decoding force conjecture completely different and incorrect targets—these include the California coast and Pearl Harbor. The timely intelligence allows Nimitz to plan and deploy forces to counter the Japanese attack.

“The enemy saw Midway as the first step in defeating the U.S. fleet and eventually removing the threat of the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor,” writes Rear Admiral Donald “Mac” Showers, USN (Retired), in the forward to the book, underlining the importance of an American victory at Midway.

Long before the war breaks out in Europe, the U.S. Navy begins preparing for combat with Japan, the only naval threat in the world, should a conflict emerge. “In this planning, Japan is called Orange and the United States Blue. Later known as War Plan Orange, Navy planning was in full swing by the 1920s,” states Carlson quoting Naval historian Edward S. Miller.

Long before the war breaks out in Europe, the U.S. Navy begins preparing for combat with Japan, the only naval threat in the world, should a conflict emerge. “In this planning, Japan is called Orange and the United States Blue. Later known as War Plan Orange, Navy planning was in full swing by the 1920s,” states Carlson quoting Naval historian Edward S. Miller.

Carlson’s work is liberally sprinkled with attributions as evidence supporting his statements. The well documented biography lists his sources in end notes so others can dig deeper if they wish. Kudos to Carlson for thorough research and documentation which is often lacking in writing today.

Unlike so many Americans who respond to the attack on Pearl Harbor by joining the Army, Navy or Marines, Rochefort is already a 23-year veteran of the Navy by 1941. He joins while still in high school in 1918. Carlson takes the reader through his early years of training and assignments. He begins his odyssey as a codebreaker with a plum assignment at Navy Main in the Code and Signal Section.

As Carlson details Rochefort’s history, the reader also gets a crash course in the history of naval intelligence as it develops. Non-navy readers may get a bit confused with details of the inner workings of the Navy, but keep reading. If you wade through the dense parts, you are rewarded with juicy tidbits of how counter intelligence evolved and the breadth of knowledge needed to decipher messages. Intercepting is the first step. Decoding is a lengthy series of time-consuming steps. According to Hollywood, it takes a few minutes to decode a message, but according to Carlson it takes days to get one even partially worked out.

As Carlson details Rochefort’s history, the reader also gets a crash course in the history of naval intelligence as it develops. Non-navy readers may get a bit confused with details of the inner workings of the Navy, but keep reading. If you wade through the dense parts, you are rewarded with juicy tidbits of how counter intelligence evolved and the breadth of knowledge needed to decipher messages. Intercepting is the first step. Decoding is a lengthy series of time-consuming steps. According to Hollywood, it takes a few minutes to decode a message, but according to Carlson it takes days to get one even partially worked out.

We get glimpses of Rochefort’s personal life. However, it seems as though it was secondary to his professional work of cryptanalysis. Everything took a backseat to work—sleep, food, reporting to superiors.

Rochefort differs from others of his rank because he is not a U.S. Naval Academy graduate. In fact, he did not finish high school. Despite his brash manner, his unorthodox approach to problem solving and his indifference over naval protocol, Rochefort is a top cryptanalyst. Those who work under his command respect and approve him. Some of those who do not work with Rochefort, work against him, according to Carlson.

There is a certain amount of intrigue—cryptanalysis aside—to the back room deals and plans made to cast doubt on his abilities and conclusions professionally and to dismiss Rochefort as head of Station Hypo. The story takes on the tinge of a conspiracy against Rochefort. This may be true. Maybe there is a conspiracy, but Carlson’s evidence is not convincing. Rather it sounds like bureaucracy gone amiss. Whether Rochefort’s naval career was intentionally derailed or not, Joe Rochefort’s War: The Odyssey of the Codebreaker Who Outwitted Yamamoto at Midway is a good read. The narrative takes readers into the core of naval intelligence’s genesis including the aspirations and personalities of key players, plus the friction they encounter with one another. Rochefort may not have been the father of naval code breaking, but he is definitely remembered as one of the early, innovative ancestors of the art.

There is a certain amount of intrigue—cryptanalysis aside—to the back room deals and plans made to cast doubt on his abilities and conclusions professionally and to dismiss Rochefort as head of Station Hypo. The story takes on the tinge of a conspiracy against Rochefort. This may be true. Maybe there is a conspiracy, but Carlson’s evidence is not convincing. Rather it sounds like bureaucracy gone amiss. Whether Rochefort’s naval career was intentionally derailed or not, Joe Rochefort’s War: The Odyssey of the Codebreaker Who Outwitted Yamamoto at Midway is a good read. The narrative takes readers into the core of naval intelligence’s genesis including the aspirations and personalities of key players, plus the friction they encounter with one another. Rochefort may not have been the father of naval code breaking, but he is definitely remembered as one of the early, innovative ancestors of the art.

You can obtain this book from your local library, interlibrary loan or from Amazon: Joe Rochefort's War: The Odyssey of the Codebreaker Who Outwitted Yamamoto at Midway.