Desert Exile: The Uprooting of a Japanese American Family

A young adult's perspective on the round up of Japanese Americans in California following the Pearl Harbor attack.

by Nancy Kerstetter

Yoshiko Uchida provides a young adult’s perspective of the aggressive round up of Japanese Americans residing in California following the attack on Pearl Harbor by the Japanese military. Desert Exile: The Uprooting of a Japanese American Family differs from other similar works because of Uchida’s age at the time of her displacement in the spring of 1942. The 20-year-old relates the events from the outlook of a typical college student seeking to complete a successful semester of studies in order to receive her diploma. Then, unforeseen horrors disrupt her life forever.

Reared in a traditional Japanese home setting, Uchida authored many books of Japanese folk tales after spending two years in Japan on a Ford Foundation Fellowship studying Japanese culture, customs, and folktales with the founders of the Japanese Folk Art Movement. Her first post high school degree was a Bachelor of Arts in English and Philosophy she earned at the University of California at Berkeley in 1942. She was unable to attend commencement because she and her family were being held at a Japanese Assembly Center at Tanforan Race Track across the bay.

Reared in a traditional Japanese home setting, Uchida authored many books of Japanese folk tales after spending two years in Japan on a Ford Foundation Fellowship studying Japanese culture, customs, and folktales with the founders of the Japanese Folk Art Movement. Her first post high school degree was a Bachelor of Arts in English and Philosophy she earned at the University of California at Berkeley in 1942. She was unable to attend commencement because she and her family were being held at a Japanese Assembly Center at Tanforan Race Track across the bay.

The meat of Uchida’s story begins on December 7, 1941, when, during a radio program the family listened to while gathered at the dining table for a meal, a frenzied voice breaks the news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Uchida’s father dismisses the report as the act of a dissident, not his former homeland, Japan. But the family soon learns Japan has attacked their new country.

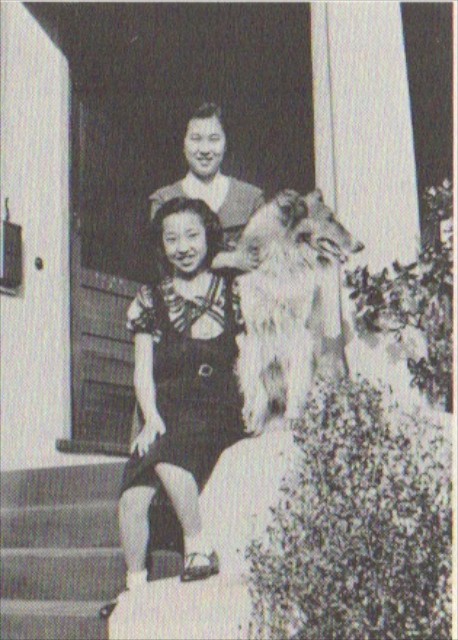

Uchida’s father had immigrated from Japan to Hawaii and then California in 1903. Her mother, a former college friend, came to join him in marriage. By 1941, they have two grown daughters, Yoshiko and Keiko. Keiko has completed college and works nearby while still living at home. Uchida’s father has become a Japanese community leader who is respected by the Issei (first generation Japanese immigrants) and Nisei (second generation Japanese Americans such as Yoshiko and Keiko’s peers). FBI agents and policemen take Mr. Uchida into custody for questioning that same day. He was not reunited with the family until he joined them in a relocation camp.

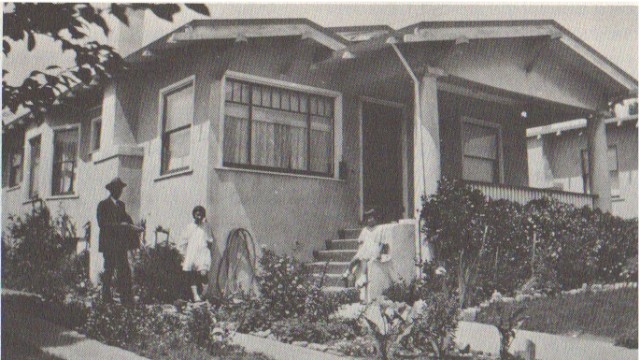

This is where Uchida’s story becomes poignant. She relates how she helps her mother and sister dispose of their home and all their property when have a slim 10-day deadline to report for detainment. With only vague instructions and guidelines of what they were allowed to bring with them, the women work frantically at the heartbreaking task of dismantling their home in time to report to the Civil Control Station located at First Congregational Church.

This is where Uchida’s story becomes poignant. She relates how she helps her mother and sister dispose of their home and all their property when have a slim 10-day deadline to report for detainment. With only vague instructions and guidelines of what they were allowed to bring with them, the women work frantically at the heartbreaking task of dismantling their home in time to report to the Civil Control Station located at First Congregational Church.

The family is assigned to Tanforan Race Track in nearby San Bruno where they are housed in a horse stall. Later Uchida and her family are moved from the verdant San Francisco area they knew so well to the dust and desert of Topaz concentration camp near Delta, Utah.

The War Relocation Administration established the camps to confine Americans of Japanese ancestry. The charges are ever brought against any of these individuals. With little time to set up adequate facilities, the camps become dismal places for family life. The relocation of thousands of innocent Japanese Americans remains one of the most flagrant, unnecessary violations of human rights for U. S. citizens in our history. Uchida expresses her disappointment and frustration in constructive ways, allowing her to retain her enthusiasm for her country while conveying the injustice of these actions.

Hardships in the primitive camps notwithstanding, she comments on the fact that her father’s Social Security pension was based on his post-camp meager wages, rather than his pre-internment ample income. This reinforces the idea that these citizens continued to suffer from this wartime action for many years—some for the rest of their lives.

Hardships in the primitive camps notwithstanding, she comments on the fact that her father’s Social Security pension was based on his post-camp meager wages, rather than his pre-internment ample income. This reinforces the idea that these citizens continued to suffer from this wartime action for many years—some for the rest of their lives.

In an era of concern for human rights both here and around the world, Americans should take time to study our own history of such violations. The seizure of Japanese Americans on U. S. soil is not widely known or understood. In 1941, such citizens were illegally taken from their homes and neighborhoods and forced to live in overcrowded, poorly constructed camps in unsanitary conditions without the benefit of good nutrition or adequate protect from the elements.They were cut off from their extended families, friends and the outside world.

Uchida tells of their self government. She writes of Topaz residents organizing schools, athletics and social activities. This reveals a determination not to be downtrodden. The resilient Japanese Americans were finally released and able to start over. That is what they had to do. They could not return to their previous lives because those lives had effectively been wiped away.

Uchida tells of their self government. She writes of Topaz residents organizing schools, athletics and social activities. This reveals a determination not to be downtrodden. The resilient Japanese Americans were finally released and able to start over. That is what they had to do. They could not return to their previous lives because those lives had effectively been wiped away.

Uchida’s story is a tale of perseverance and coping with tragic circumstances. Because she was there to live it and observe others around her, we have a rich account of what really took place behind barbed wire in remote locations patrolled by armed guards. We have insight into the Issei and Nisei minds as they maneuvered through this difficult passage of American history.

There are still unanswered questions regarding how to avoid such a travesty in the future.

You can obtain this book from your local library, inter-library loan or from Amazon.