Japanese Way of Supporting the Weak

Creative ways the Japanese underpin weak limbs--in both the young and the old.

by Bob Kerstetter

An old friend in Japan recently suffered an amputation.

When you think it over—and under—and through—the loss causes no surprise. During a pre-amputation visit you clearly noticed his weakened appendage—as we sometimes colloquially call it. It stayed useful only when aided by a heavily reinforced brace. While your friend photographed handsomely before—and still appears healthy after his surgery—you could easily envision the demise of his limb.

Still, seeing him without his crutch—and with his part missing—creates a surge of sadness throughout your body. As an American, you can hardly mask your emotions behind the acceptance you sometimes see in Japanese stoicism.

Your friend captured your attention by the artful way he fit into his surroundings. Even his external prop gracefully blended with his environment. You approached from a distance and climbed a few steps. Despite his unusual appearance, you soon felt comfortable. While you visited only for a few minutes, his compelling attractiveness called you back two or three times over several days. You sometimes snapped his picture. You assumed he felt positive about your interest. Then you went home.

Returning to Japan after 18 months in the US, you observe his loss. You sit on the stairs next to him and mourn—but not for long. He seems to acknowledge and receive your sorrow. Letting go, you enjoy his aged goodness and begin to understand his wholeness.

Your friend lives below an inclined moat wall built 400 years ago to protect Wakayama Castle. His missing limb once paralleled the steps leading to the top. Nearby spreads the beautiful ruins of Ninomaru (二の丸) Gardens—the outer citadel gardens—where the feudal master conducted business at the base of Mt. Torafusu (虎伏山), the castle mountain.

Before you and your friend originally met, you passed by several others of like kind in similar conditions—noticing from a distance their ailments, injuries and artificial underpinnings. Looking away, you preferred to concentrate on their healthy companions. Yet, these first contacts helped you begin to observe and appreciate the Japanese way of supporting—rather than discarding—the weak.

Two branches of a Japanese cherry tree—sakura (さくら, 桜)—receive manmade support as they stretch above the steps rising to the top of a moat wall at Wakayama Castle, Wakayama, Japan, Kansai Region. The tree lost one of its limbs sometime during the 18 months after the photo date.

The Japanese use many means of caring for trees and encouraging growth into old age. Their love of arboriculture partially grows from the familiar forests covering nearly seven-tenths of their country.

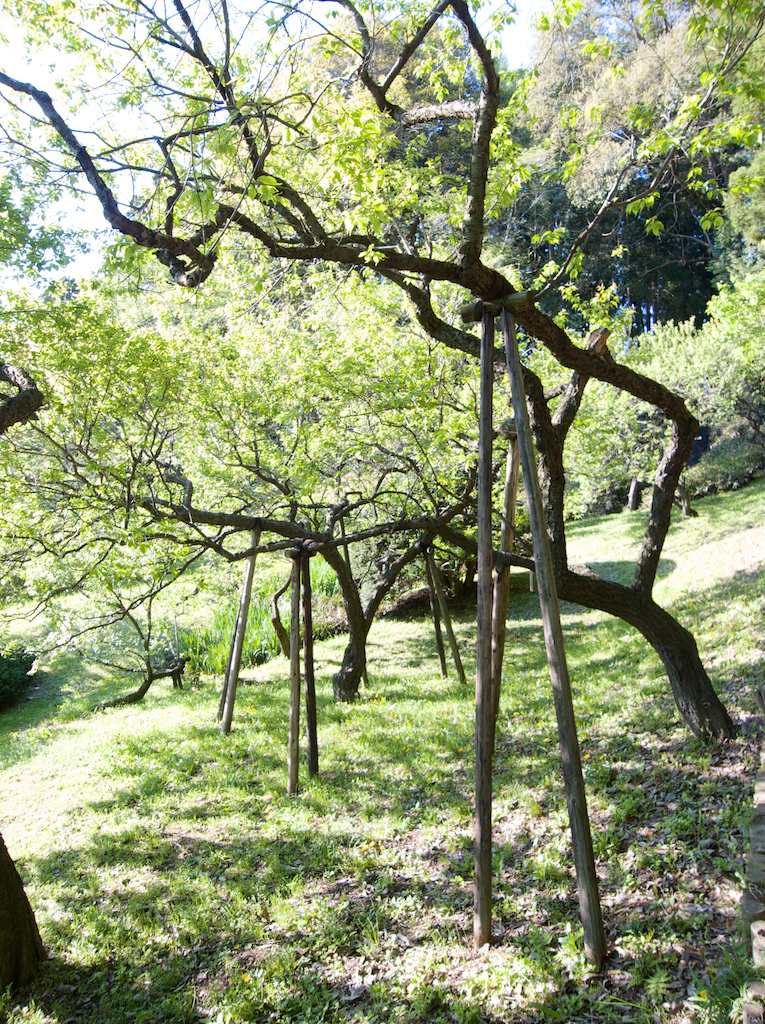

Throughout Japan you can see hundreds of young and old trees benefiting from human-made supports, fashioned from bamboo and wood timbers. For the young, these structures help manage their growth. Old trees often receive bracing for long heavy branches, helping extend for years their beauty and usefulness.

After cracking open its host igneous rock for 300 to 400 years, the Rock Splitting Cherry Tree—石割桜(ishiwarizakura)—in Morioka Japan now receives support for its longest and heaviest limbs. Morioka serves as the capital city of Iwate Prefecture in the Tohoku region of Japan.

A heavy timber brace keeps an evergreen from touching the earth near Katsurahama Beach—桂浜—on the south side of Kochi City on the Japanese island of Shikoku.

Tall supports hold up the limbs of plum trees in the Kairaku-en—偕楽園—an Edo Era garden located in Mito City, Ibaraki Prefecture, northeast of Tokyo.

A 300-year-old pine—named 300 Year Pine—spreads across the ground with its branches lifted off the earth by many wooden supports. Yes, all of this greenery—except for the deciduous tress in the upper-left background—comes from one old pine tree. It resides at Hamarikyu Garden—浜離宮恩賜庭園—in Tokyo, Japan.